Aston All Saints - A Rich History

About 700 AD, the people of Aston embraced Christianity and built a church; probably of wood and wattle. It is recorded in the Doomsday Book that “a church is there, and a priest”. There are traces of that church beneath the present building. After the Norman Conquest in 1066, the Norman Lord erected a Hall and rebuilt the church in stone. Since then the building has been extended a number of times although some of the original early 12th century stonework remains.

In the 13th century, the church was probably a rectangular building covering what is now the Nave. There would have been a solid west wall where now there is a tower, and solid walls instead of the arches on either side. Narrow slits in the walls would have given a little light that would have reflected from the lime washed walls. The decorative stonework would have been coloured in red, blue and yellow paint. Rushes would have covered the earth floor and a patch of disturbed earth would indicate a recent burial. At the east end of the church (where the altar is now) there would have been an apse – a semi-circular wall with a roof like a dome. The altar would have been under the dome.

The building was extended, and the side aisles built, at various times during the medieval period. Because of this piecemeal extension, the piers (pillars) and the arches are in different styles, two round, two octagonal, possibly due to the Normans favouring variety. Neither do the Nave arches match; the south-east arch is early Gothic and pointed while the others are in Norman rounded style, with typical carved decorations.

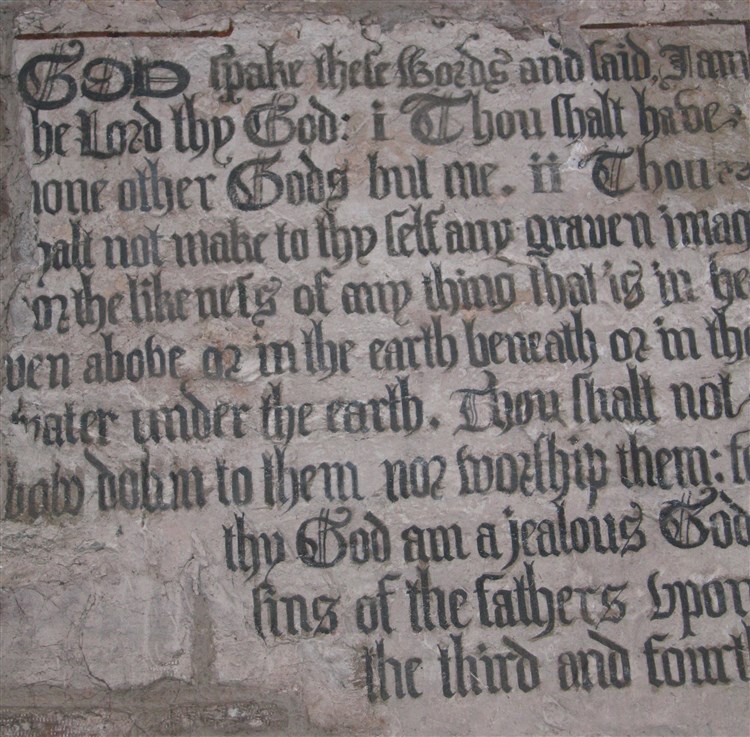

The walls of the aisles in the nave would have been plastered and colourfully decorated with pictures or with uplifting texts. There are fragments of these painted texts on the wall of the north aisle, one of which dates from 1604. It was revealed when the plaster was being removed from the wall in the late 20th century.

Fragments of painted text remaining on the north aisle wall

The chancel was built for William de Melton, Archbishop of York and Lord Chancellor of England. He bought the Manor of Aston and built a Hall as residence when visiting this part of his Archdiocese in 1332. The original apse was removed, the Gothic style arch constructed and the church extended again. This extension differs from the rest of the church in that the outside is faced with limestone.

The chancel exterior

The altar is made of solid (and extremely heavy) stone on top of a wooden base was placed under the east window that is why there is a squint (an angled opening) to the right of the chancel arch. This gave a view of the altar from the south aisle. The 19th century Sanctuary Lamp still hangs over where the altar was situated before it was moved in 1957. The chancel was built with two doors. One door was used by the clergy (it now leads into the choir vestry). The other door was the Lord of the Manor’s entrance, with a path across the graveyard to the 16th century gateway to Aston Hall. This is the door your can see in the picture above. The lord’s entrance gave access to his private pew, which was just to the east of the squint. It had its own fireplace, which was discovered when the wall by the squint was re-plastered in the 1990s.

The altar, viewed from the chancel

The alter uncovered, showing the large stone and wooden base

The squint view through to the Nave

After the chancel was built, the east end of the south aisle became a Lady Chapel and in medieval times an altar stood against the wall. There is a piscina (stone basin used for washing the Communion vessels) built into the south wall. The Lady Chapel was a favoured burial place and a number of Rectors are buried there. At the opposite side of the building (the east end of the north aisle – where there is now a door into the choir vestry) was the Melton family’s Requiem Chapel.

The porch was constructed in the 14th century. The badly eroded figures on either side of the entrance are effigies of King Edward III and Queen Phillipa. This dates the porch to no later than 1369 – the year the Queen died. A 1900 newspaper reported that the carvings were in near perfect condition but the acid rain later in the 20th century has almost obliterated them. It is probable that the stone benches were used when teaching children, before the village had a school.

The tower was erected sometime between 1350 and 1450. It is part of the Melton additions to the church. The tower is about eighty feet in height and overlooks all the other buildings in the Parish. It has had many uses over the centuries. In its early days it provided a look out and refuge in times of trouble: flattened musket balls found outside its walls are evidence of that. It was also used as a temporary gaol (detention centre) to hold people awaiting trial.

In around 1552 there were six bells in the tower: the surviving bell-rope holes indicate that the bells were swung. Unfortunately the foundations are not very solid and swinging the bells also rocked the tower. There are now just three bells, two of which date from 1784 and which are rung by striking the rims with hammers worked by the pull ropes instead of being swung due to the unstable foundations. One of them is connected to the Parish clock and strikes the hours. The clock is weight powered and requires winding two or three times each week. In the mid 20th century, mining subsidence caused the tower to tilt away from the nave and that stopped the pendulum from swinging. Later the tower tilted back to the perpendicular and the clock became operational again.

By the 18th century, the building had assumed its present shape. In 1771 oak pews were fitted to wooden flooring in the nave; these pews remained in use for over 200 years, until they became decayed and damp and were replaced by the current pews that came second hand from Holy Trinity Church in Rugby. In about 1790, a gallery was erected in the base of the tower. It lasted about 90 years and during that time it was used by musicians, provided space for additional seating and was home to a barrel organ. At that time there was an ornate wooden screen dividing the tower from the nave.

The nave, showing pews and the tower at the rear

The Victorians added what is now the choir vestry. For many years it housed a small pipe organ, built by Albert Keates, from his organ works on Charlotte Road, Sheffield (NPOR N01907), but in 2001 this was removed and replaced with the present electronic instrument; a two manual Eminent instrument. Remnants of the original organ were made into a picture now hanging in the choir vestry. It is always a shame to loose a real pipe organ however the original instrument required a great deal of investment and had been described by the Organ Advisor for the area as "an instrument of no historic, musical or aesthetic value". The present electronic instrument is sufficient for the job and flexible enough to meet the demand of modern church music.

The remains of the Keates organ residing in a picture frame

The pulpit was moved to its present position in the respond of the Eastern arch of the North side of the Nave in 1962 leaving traces of its original position at the base of the chancel arch. The plainness of its design suggests it to be from the 17th Century.

The most recent addition to the church is the Narthex, which was built in 1989 and is reached through a new oak door in the north wall. It provides a toilet, kitchen and a meeting room.

There are a number of memorials in the church to Lords of the Manor, and from them it is possible to trace the families that held the estate. On the left side of the chancel arch is a brass memorial to Sir John Melton (the last Melton Lord of the Manor), and his coat of arms. He died during the reign of King Henry VIII.

Dorothy Melton inherited the estate and married a George Darcy. The Darcys’ resided in Aston for many years and the last of them, Good Sir John, inherited the Manor in 1602. He married four times: there are effigies of him and his first three wives on the north wall of the chancel. He was left without an heir and his fourth wife outlived him. She married Sir Francis Fane and continued to live in Aston. The monument to their ‘many sonnes and daughters’ is on the south wall of the chancel.

Good Sir John Darcy and his first three wives

The last Lords of the Manor were the Verelsts. Harry Verelst succeeded Clive of India as Governor of Bengal, and when he retired he first rented and then bought the Manor in 1770. Only a year later- on Christmas Day 1771 – the old Aston Hall burned down. The East stained glass window was salvaged, and installed in the church in the Lady Chapel. It depicts the Arms of the Darcy family (and families related by marriage). There are brass plaques in memory of later members of the Verelst family on the screen in the tower. In 1928 the Manorial Estate was divided up and sold off – the Aston Hall being converted to a women’s mental hospital. It is now the Aston Hall Hotel.

The centre stained glass window of the Lady Chapel

The font dates from about 1400. It was moved from under the tower to its present location in 1957. The carved figures on the base are thought to represent King Herod, intent on killing the baby Jesus and a guardian angel warning Joseph to flee with the Holy Infant to Egypt. The lead lined bowl is octagonal with battlements carved around its top and large enough to immerse an entire baby which was the custom in days gone by.

The Aston font

William Mason

Mason was probably Aston’s most famous Rector. There is a monument to him in the chancel and a much grander one in Westminster Abbey’s Poets Corner. He was appointed (by Robert Darcy, the Fourth Earl of Holdernesse) in 1754, and remained for 43 years. He was responsible for building the Old Rectory (which still survives – the large building opposite the church entrance). Amongst his visitors to the Rectory were Horace Walpole, and his close friend the poet Thomas Gray, who penned ‘Elegy in a Country Churchyard’. On the south wall of the church are two plaster reliefs, commemorating Mason and Gray, which were originally in the summer house of the Rectory.

On the north side of the Sanctuary is a mid 19th century copy of a 4th century Florentine relief of the Madonna and Child. It is thought to be a section of a triptych; the other two parts of this work are in a St Petersburg Hermitage Museum, it is attributed to Giovanni Bastionini. There are chairs in the Sanctuary from the 16th, 17th, 18th and 19th centuries. The altar, which may date from Saxon times, was about two feet wider than it is now. During the Edward VI purges the stone altar top was taken out of church and hidden to prevent its destruction. It was rediscovered (broken in two) in the churchyard in 1957.

Florentine relief of the Madonna and Child donated by a previous Rector

On the wall of the tower are large boards recording charitable bequests. By today’s standards the amounts seem trivial but when they were made, a worker was earning about £10 a year. Much of the original investments were lost but Aston Charities still aids needy parishioners and local groups.

Please come and visit this wonderful building for a service and take a look around afterwards.

Further details of the building can be found at the website here.